As defined on the Positive Peace Warrior Network website, Kingian Nonviolence is “a philosophy and methodology that provides the knowledge, skills, and motivation necessary for people to pursue peaceful strategies for solving personal and community problems.”

Formulated by Dr. Bernard Lafayette and David Jehnsen, Kingian Nonviolence is one of the foundational philosophies of nonviolence the Gandhi Institute utilizes to teach community members about the significance of nonviolence to the construction of a just, equitable world.

Grounded in six principles, the second principle of Kingian Nonviolence reads “The Beloved Community is the Framework for the Future”, with the beloved community essentially being “…a world where people of all races, genders, cultures and generations are living in unity with each other.”.

While I wholeheartedly agree with the radical humanists sentiments conveyed by the second principle, there is a, perhaps intentional, vaguery encircling the second principle’s proposed method for the assembling of beloved community.

Amidst this vaguery, I offer radical Black feminism, in both theory and action, as a method by which beloved communities may blossom. Unlike the feminisms deployed by various groups of white women uncritical of how white supremacy operates in their lives, also known as “white feminism”, radical Black feminism sprang from the minds of various Black women dissatisfied with the racism within the, often very white, women’s movements and the sexism within male-led organizations advocating “Black Power”.

By taking into consideration the various intersections in which systems of domination operate, radical Black feminists broke ground in liberatory struggle by offering a framework which rejected narrow-minded thinking in relation to identity, paving way for nuanced scrutinizations of the world’s social ills, especially in reference to the plight of Black women.

In her piece entitled Resting in Gardens, Battling in Deserts1, humanities and political science professor of Williams College, Joy James, gives both historical context to radical Black feminist thought and action, as well as a sampling of projects taken up by those who operate from the radical Black feminist banner. From actions taken to dismantling military and prison industrial complexes, to challenging global state governments to honor human rights law, James’ article is a non-exhaustive overview of radical Black feminist agendas.

One may argue that these agendas may be, and are often, acted out detached from a radical Black feminist framework. However, agendas which do not operate from an anti-racist, feminist framework are extremely likely to reproduce violence upon people marginalized because of race and/or gender; these people often being Black women and other women of color.

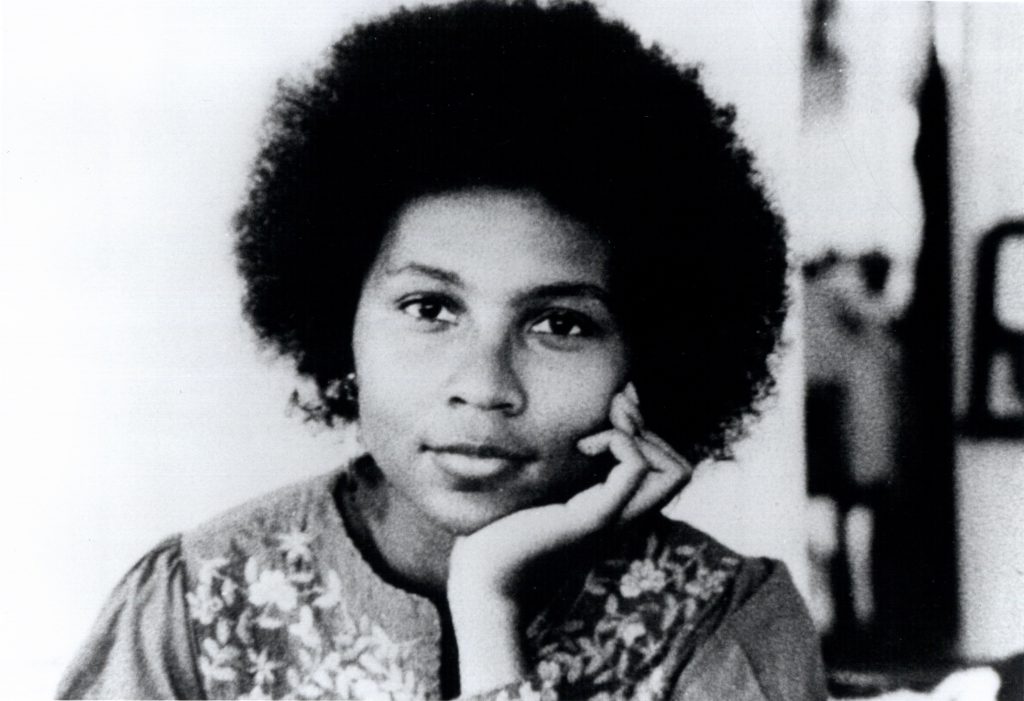

bell hooks, the widely acclaimed Black feminist scholar, coined the term imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy in order to give language to the ever-present, interlocking systems of domination undergirding our society. And, as suggested by both the second principle of Kingian Nonviolence and The Combahee River Collective’s statement on radical Black feminism, when one system of domination is operating, more are never far behind.

The expansive, and ever expanding, range of ideas grappled with by radical Black feminist thought, from sexuality to art, offers a social justice framework capable of considering the predicaments of the multiply marginalized among us; a methodology established for incorporating the needs of the most downtrodden into the blueprint for a transformed society.

So, here, I implore the reader to study the works of radical Black feminists such as Audre Lorde, Angela Davis, June Jordan, bell hooks, Patricia Hill Collins, Michele Wallace, Barbara Smith, Michelle Cliff, Anna Julia Cooper, and countless others. Support organizations that operate from a radical Black feminist framework, such as the Black Youth Project 100, the Audre Lorde Project, or Black Girl Dangerous.

The radical humanism inherent to radical Black feminism often goes misunderstood, or outright disregarded. If we are to build beloved communities of integrity, radical Black feminism cannot be ignored. “Liberation” means nothing if it doesn’t apply to everyone.

by Malik Thompson

References:

1. James, Joy. “Resting in Gardens, Battling in Deserts: Black Women’s Activism.” Race and Resistance: African Americans in the 21st Century. (Ed. Herb Boyd. Cambridge: Southend Press, 2002.) 67-77. Print